When you have heart failure, fluid builds up in your body. Diuretics - often called water pills - are one of the most common treatments to get rid of that extra fluid. But there’s a hidden risk: hypokalemia, or dangerously low potassium levels. It’s not rare. About 1 in 4 heart failure patients on loop diuretics like furosemide end up with potassium below 3.5 mmol/L. And when that happens, your risk of irregular heartbeats, hospital readmissions, or even sudden death goes up by 50% to 100%.

Why Diuretics Lower Potassium

Loop diuretics like furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide work in the kidneys by blocking sodium reabsorption. That sounds good - less sodium means less fluid. But here’s the catch: when sodium gets flushed out, potassium follows. The kidneys don’t distinguish between the two. They dump both into the urine. This effect gets stronger the higher the diuretic dose, and it doesn’t stop after the first pill. Over time, your body adapts. You develop tolerance. That means you need more diuretics to get the same result - and you lose even more potassium with each dose.It’s worse if you’re also taking other potassium-wasting drugs - like thiazides (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide) or laxatives. Even dietary sodium restriction, which is often recommended for heart failure, can make things worse. Cutting salt triggers your body to release aldosterone, a hormone that pushes even more potassium out through the kidneys. So, the very thing meant to help - reducing fluid - can accidentally push your potassium into the danger zone.

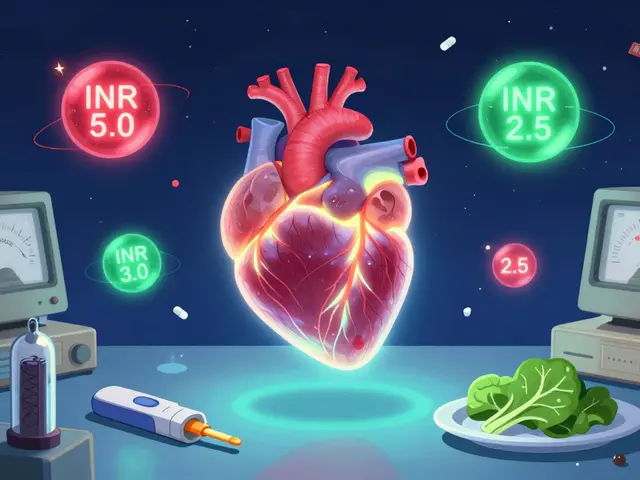

What Counts as Low Potassium?

Normal potassium levels sit between 3.5 and 5.5 mmol/L. In heart failure patients, staying above 3.5 mmol/L is non-negotiable. Below that, your heart becomes electrically unstable. Ventricular arrhythmias become more likely. Studies show that patients with potassium under 3.5 mmol/L have a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of dying from heart-related causes.It’s not just about the number. It’s about how fast it drops. A sudden dip from 4.2 to 3.1 in a few days is more dangerous than a slow, steady decline. That’s why regular blood tests matter - not just once a year, but every time your diuretic dose changes, or if you feel weak, dizzy, or notice your heart skipping beats.

How to Fix Low Potassium

The first step is simple: replace what’s lost. For mild hypokalemia (3.0-3.5 mmol/L), doctors usually prescribe oral potassium chloride. A typical dose is 20 to 40 mmol per day, split into two doses to avoid stomach upset. Don’t just grab potassium supplements off the shelf - the wrong form or dose can be harmful. Always follow your provider’s instructions.If your potassium is below 3.0 mmol/L, you may need IV replacement. That’s done in a hospital with continuous ECG monitoring. Giving potassium too fast can stop your heart. Slow and steady wins here.

But replacing potassium is only half the battle. You also need to stop the leak. That’s where potassium-sparing medications come in.

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs)

Spironolactone and eplerenone aren’t just potassium boosters - they’re life-savers. The RALES trial, a landmark study from the late 1990s, showed that adding spironolactone to standard heart failure treatment cut death risk by 30% in patients with severe heart failure. One reason? These drugs block aldosterone, the hormone that drives potassium loss. They help your kidneys hold onto potassium instead of flushing it out.Guidelines now recommend starting spironolactone at 12.5-25 mg daily for patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Eplerenone, at 25 mg daily, is an alternative, especially if you’re prone to side effects like breast tenderness (a known issue with spironolactone). These drugs are not optional add-ons - they’re standard of care for most HFrEF patients, even if potassium is normal.

What About SGLT2 Inhibitors?

In the last five years, a new class of drugs has changed heart failure treatment: SGLT2 inhibitors. Originally designed for diabetes, drugs like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin have proven powerful in heart failure - even if you don’t have diabetes.How do they help with potassium? They reduce fluid overload without causing potassium loss. Clinical trials show they lower the need for diuretics by 20-30%. Less diuretic = less potassium washed out. They also improve heart function directly, reduce inflammation, and lower hospitalization rates. The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guidelines now recommend them for all heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction, regardless of diabetes status.

They’re not magic. They can cause dehydration or genital infections. But for potassium balance? They’re one of the safest tools you have.

Timing and Dosing Matter

Giving furosemide once a day may seem convenient, but it’s not ideal. The drug’s effect spikes quickly, then fades. That causes big swings in sodium and potassium levels. Studies show that splitting the dose - say, 20 mg in the morning and 20 mg at noon - leads to more stable electrolytes and better fluid control.For patients needing high doses, adding a low-dose thiazide like metolazone (2.5 mg) can help. But this combo is a double-edged sword. It boosts diuresis, but it also increases potassium loss. If you’re on this combo, you need weekly potassium checks until levels stabilize.

Diet and Lifestyle Adjustments

You can’t rely on pills alone. Food matters. Bananas, oranges, spinach, potatoes, and beans are rich in potassium. But don’t go overboard. Too much potassium can be dangerous too, especially if your kidneys aren’t working well.Sodium restriction is still important, but aim for 2-3 grams per day - not less. Going below that can trigger aldosterone spikes and worsen potassium loss. Talk to a dietitian. They can help you build meals that reduce fluid without starving your body of potassium.

Also, check your other meds. Are you taking corticosteroids? Laxatives? Antibiotics like amphotericin B? These can all drain potassium. Your doctor needs to know everything you’re taking - even over-the-counter stuff.

When to Get Help

If you feel unusually tired, weak, or notice your heart racing or skipping, get checked. These aren’t normal side effects. They’re red flags. Don’t wait for your next appointment. Call your provider or go to urgent care. A simple blood test can tell you if your potassium is dropping.Also, if you’ve had a recent hospital stay for heart failure, your potassium is likely to be low. Many patients leave the hospital with potassium under 3.5 mmol/L. That’s why follow-up blood work within 7 days is critical.

Monitoring Schedule

Here’s what works in real-world practice:- At start of diuretic therapy: check potassium within 3-5 days

- After any dose increase: check within 1 week

- Once stable on chronic therapy: check every 1-3 months

- During illness, vomiting, diarrhea, or reduced food intake: check immediately

- If you’re on an MRA or SGLT2 inhibitor: check every 3 months (even if you feel fine)

Some patients do home finger-prick potassium tests, but those aren’t reliable yet. Stick to lab tests. Accuracy matters.

The Bigger Picture

Managing hypokalemia isn’t just about numbers. It’s about protecting your heart from silent, deadly rhythms. It’s about balancing fluid removal with electrolyte safety. It’s about using the right drugs at the right time - not just more pills.Today, heart failure treatment is smarter than ever. We don’t just push fluid out. We protect the heart while we do it. MRAs, SGLT2 inhibitors, and smart diuretic dosing have turned what used to be a dangerous side effect into a manageable part of care.

But it still takes vigilance. You can’t ignore potassium levels just because you’re feeling better. Your heart doesn’t know you’re on medication. It only knows if your potassium is low - and that’s all it needs to trigger a crisis.

Can I just take a potassium supplement instead of changing my meds?

Oral potassium supplements can help with mild low levels, but they don’t fix the root cause. If your diuretic is making you lose potassium, you’ll keep losing it - no matter how many pills you take. Adding a potassium-sparing drug like spironolactone is far more effective and safer long-term. Supplements also carry risks - too much potassium can cause dangerous heart rhythms, especially if your kidneys aren’t working well. Always use supplements under medical supervision.

Do all diuretics cause low potassium?

No. Loop diuretics (furosemide, bumetanide) and thiazides (hydrochlorothiazide) are the biggest culprits. But potassium-sparing diuretics like spironolactone, eplerenone, and amiloride actually help keep potassium up. Some patients get a combination pill with a loop diuretic and a potassium-sparing agent to balance the effects. Ask your doctor if this option is right for you.

Can I eat more bananas to fix low potassium?

Food helps, but it’s not enough. One banana has about 400 mg of potassium - that’s less than 10 mmol. A typical daily replacement dose is 40-80 mmol. You’d need to eat 8-16 bananas a day, which isn’t practical or safe. Plus, your body absorbs potassium from food slower than from supplements. Relying on diet alone won’t correct a significant deficiency. Use food as support, not treatment.

Why do I need to check potassium if I feel fine?

Low potassium doesn’t always cause symptoms until it’s dangerously low. By the time you feel weak or your heart skips, you’re already at risk for a serious arrhythmia. Many people with hypokalemia feel nothing at all. That’s why regular blood tests are non-negotiable. It’s like checking your blood pressure - you don’t wait for a headache to do it.

Is hypokalemia more dangerous in older patients?

Yes. Older adults often have reduced kidney function, which makes it harder to regulate potassium. They’re also more likely to be on multiple medications that affect electrolytes. Studies show that patients over 75 with heart failure and low potassium have higher rates of hospitalization and death than younger patients with the same levels. Extra caution and more frequent monitoring are needed in this group.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors replace diuretics entirely?

No. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce fluid overload and lower diuretic needs by about 20-30%, but they don’t eliminate the need for them - especially in patients with severe congestion. Think of them as partners, not replacements. They make diuretics work better and safer, not unnecessary. Most patients still need some form of diuretic, but with SGLT2 inhibitors, they can often use lower doses and have fewer side effects.

Chris Buchanan

December 24, 2025 AT 04:57So let me get this straight - we’re giving people pills to flush out fluid, but then pretending we didn’t just drain their potassium like it’s a soda can left in the sun? Classic medical whack-a-mole.

claire davies

December 24, 2025 AT 09:19Okay, I’ve been managing HF for 7 years now, and this post? It’s the first time someone actually explained why I feel like a deflated balloon after my furosemide dose. I used to think my weakness was just ‘aging’ - turns out it’s my potassium doing the cha-cha out of my kidneys. I started eating more spinach and sweet potatoes, and honestly? My legs stopped feeling like wet noodles. Also, I swear by my 12.5mg spironolactone - it’s like my heart finally got a hug. Don’t sleep on MRAs. They’re not ‘optional’ - they’re the quiet heroes in this whole mess.

Raja P

December 24, 2025 AT 23:38From India, where potassium-rich foods like bananas and coconut water are everywhere - but still, my doc insisted on supplements because my levels kept crashing. I used to think ‘eat more bananas’ was the solution, but now I get it: food helps, but it’s like trying to fill a bathtub with a teaspoon. The real fix is blocking the leak, not just pouring in more water. Spironolactone changed my life. No more dizziness. No more ER trips. Just quiet stability.

Joseph Manuel

December 25, 2025 AT 03:54The assertion that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce diuretic requirements by 20–30% is statistically significant but clinically overstated in real-world populations with advanced renal impairment. The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial excluded patients with eGFR <30 mL/min, yet these patients constitute nearly 40% of the HF population. The generalization of guideline recommendations without stratification by renal function is methodologically unsound.

Andy Grace

December 26, 2025 AT 23:10I’ve been on furosemide for 5 years. I didn’t know potassium could drop so fast. My last blood test showed 3.2 - I thought I was just tired from work. Now I check mine every 6 weeks. I also take my spironolactone with breakfast, like my nurse said. Small things, but they matter.

Delilah Rose

December 27, 2025 AT 11:01I used to think hypokalemia was just a lab number that got ignored until someone went into VFib. But after my mom almost died from an arrhythmia while on high-dose diuretics, I became obsessed with electrolytes. It’s not just about potassium - it’s about the whole orchestra: sodium, magnesium, aldosterone, even hydration status. And honestly? The biggest game-changer wasn’t the pill - it was learning to read my own body. Dizziness? Weakness? Heart fluttering? That’s not ‘just tired’ - that’s your heart screaming. I started tracking my symptoms in a little notebook. It helped my cardiologist see patterns no lab could. Don’t underestimate the power of patient-led observation. You’re not just a patient - you’re the most important data point in your own story.

Spencer Garcia

December 28, 2025 AT 00:45Spironolactone first. Then SGLT2i. Then adjust diuretics. That’s the order. Don’t skip step one.

Abby Polhill

December 28, 2025 AT 06:15It’s fascinating how the RALES trial’s 30% mortality reduction was mediated not just by potassium sparing but also through fibrosis modulation and reduced neurohormonal activation - the mineralocorticoid receptor’s pleiotropic effects extend far beyond electrolyte balance. The fact that eplerenone showed similar outcomes with fewer gynecomastia events underscores the importance of receptor selectivity in chronic HF pharmacotherapy. We’re moving beyond symptomatic management into true disease-modifying therapy.

Rachel Cericola

December 29, 2025 AT 03:45Listen up. If your doctor isn’t prescribing spironolactone or eplerenone to your HFrEF patient - and they’re not on an SGLT2 inhibitor - they’re practicing medicine from 2005. This isn’t ‘new research.’ This is standard of care. You’re not ‘being cautious’ by avoiding MRAs - you’re risking death. I’ve seen too many patients get discharged from the hospital with potassium at 3.1 and no plan. That’s not care. That’s negligence. Stop treating hypokalemia like a side note. It’s the silent killer in plain sight. Demand the right meds. Push back. Your heart isn’t asking for permission - it’s begging for help.

Blow Job

December 29, 2025 AT 07:38I’m 68, on diuretics since 2018. My potassium dropped to 3.0 after a bad bout of the flu. I thought I was just sick. Turned out I was one heartbeat away from cardiac arrest. Now I take my spiro every morning, eat a banana with my oatmeal, and get blood drawn every 8 weeks. No drama. No panic. Just smart. This post saved me. Thank you.

Christine Détraz

December 30, 2025 AT 01:18My dad’s on all of this - furosemide, spironolactone, dapagliflozin. He says he feels better than he has in years. But he still forgets to get his labs done. I set a monthly phone reminder for him. It’s not glamorous, but it’s life-saving. Sometimes, the best care is just showing up - with a calendar, a banana, and a little stubborn love.

John Pearce CP

December 31, 2025 AT 17:00It is profoundly concerning that contemporary clinical guidelines, influenced by pharmaceutical-sponsored trials, promote the indiscriminate use of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and SGLT2 inhibitors in populations with borderline renal function, thereby exposing patients to potentially life-threatening hyperkalemia. The erosion of clinical judgment in favor of algorithmic prescribing constitutes a dangerous precedent in modern cardiology. The patient is not a data point. The heart is not a machine. Primum non nocere.