Getting a generic drug approved isn’t just about matching the brand-name pill’s ingredients. It’s about proving your version delivers the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same rate. That’s where bioequivalence (BE) studies come in. But here’s the catch: if your study is underpowered or has the wrong number of participants, you’ll fail-even if your drug works perfectly. Many generic drug developers lose months and hundreds of thousands of dollars because they got the sample size wrong. It’s not guesswork. It’s math. And if you don’t do it right, regulators will reject your application.

Why Sample Size Matters More Than You Think

In a typical clinical trial, you’re trying to prove a drug is better than a placebo. In a BE study, you’re trying to prove two drugs are the same. That sounds easier, but it’s actually trickier. You’re not looking for a big difference-you’re looking for a tiny one, and you need to be 90% sure you’re not missing it.

Imagine testing two versions of a blood pressure pill. One is the brand, one is your generic. Both should give the same peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC). The FDA and EMA say the test drug’s values must fall between 80% and 125% of the reference drug’s values. That’s your equivalence range. But what if your study only has 15 people? Even if your drug is identical, random variation in how people absorb the medicine might push one or two results outside that range. Your study fails-not because the drug is bad, but because you didn’t test enough people.

On the flip side, if you use 150 people when 30 would’ve been enough, you’re wasting money, time, and exposing more volunteers to unnecessary procedures. Regulators hate both scenarios: underpowered studies that fail, and overpowered ones that are wasteful.

The Three Numbers That Decide Your Sample Size

There are three key numbers you must nail down before you even recruit your first participant:

- Within-subject coefficient of variation (CV%) - This measures how much a person’s own response varies from one dose to another. If someone’s Cmax jumps from 100 to 140 ng/mL on two identical doses, that’s high variability. CV% for most drugs ranges from 10% to 35%. For highly variable drugs (like warfarin or clopidogrel), it can hit 40% or higher.

- Geometric mean ratio (GMR) - This is your best guess of how your test drug compares to the reference. Most generic manufacturers assume 0.95 to 1.05. If you assume 1.00 (perfect match), but your real ratio is 0.92, your sample size calculation will be off by 30% or more.

- Target power - This is the probability your study will correctly show equivalence if it’s true. The EMA accepts 80% power. The FDA often expects 90%, especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs like digoxin or levothyroxine.

These three numbers feed into a formula that spits out your required sample size. You don’t need to memorize it, but you must understand how each one affects the result.

Real-World Examples: How CV% Changes Everything

Let’s say you’re developing a generic version of a common statin. Your pilot study shows a CV% of 20% for AUC and a GMR of 0.98. You want 90% power.

Using a standard BE sample size calculator, you get: 26 subjects.

Now change only the CV% to 30%. Same GMR, same power. Result? 52 subjects.

Double the variability, double the sample size. That’s not linear-it’s exponential. And if your CV% is 40%? You’re looking at over 100 subjects. That’s not just expensive-it’s often impossible to recruit.

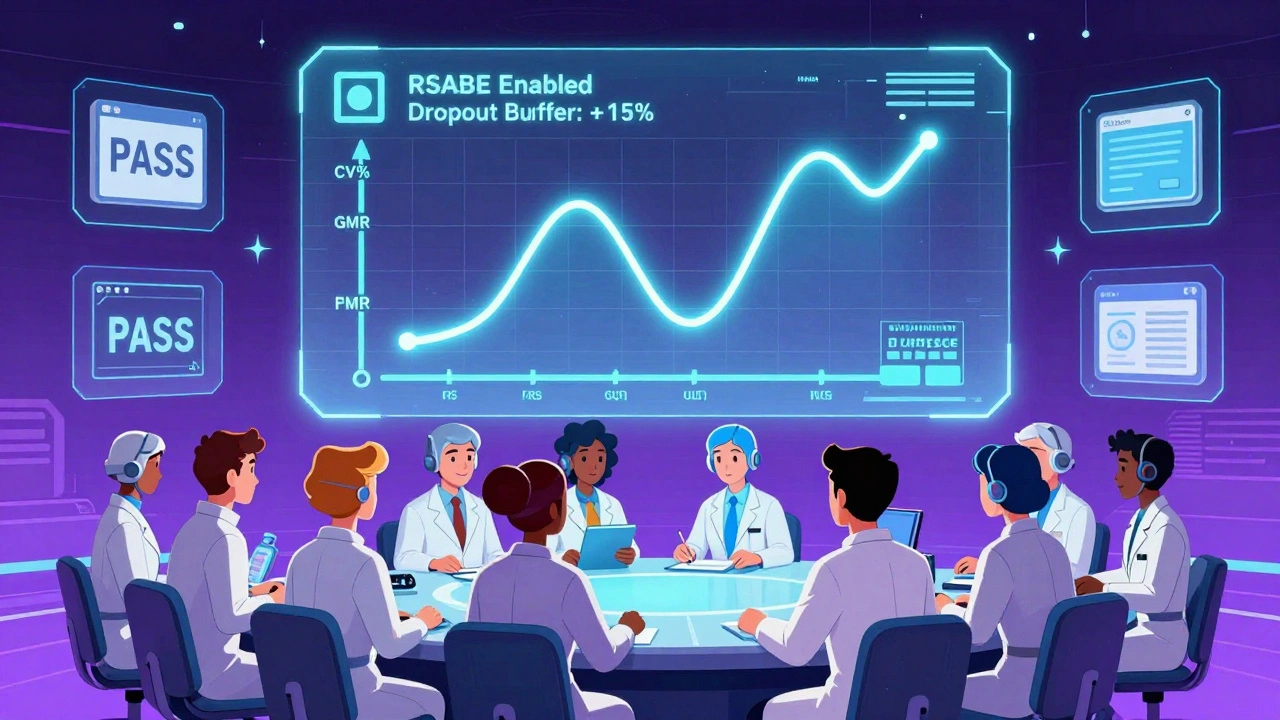

This is why regulators created reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). For highly variable drugs, the equivalence range widens based on how variable the reference drug is. If your drug’s CV% is above 30%, you might get away with 24-48 subjects instead of 100+. But you need to prove the variability is real. You can’t just claim it-you need data from pilot studies or published literature.

What Regulators Actually Look For

The FDA doesn’t just check your final numbers. They check your paper trail. In their 2022 Bioequivalence Review Template, they list exactly what you need to include:

- Software used (e.g., PASS, nQuery, FARTSSIE)

- Version number of the software

- Input parameters: CV%, GMR, power, equivalence limits

- Justification for those inputs-where did you get the CV% from?

- Adjustment for expected dropouts (usually +10-15%)

- Whether you calculated power for both Cmax and AUC jointly

Here’s the kicker: in 2021, 18% of rejected BE submissions failed because of incomplete documentation. Not because the math was wrong-because they didn’t show their work.

And don’t assume literature values are safe. The FDA reviewed 147 BE submissions and found that 63% of researchers used published CV% values that were too low. On average, those literature values underestimated true variability by 5-8 percentage points. That’s enough to tank your study.

Common Mistakes That Sink BE Studies

Here are the top three mistakes I’ve seen in over 200 BE study designs:

- Assuming a GMR of 1.00 - Real-world generics rarely hit perfect equivalence. If your drug’s true ratio is 0.95 and you designed for 1.00, you need 32% more subjects. Always use conservative estimates.

- Ignoring joint power - You have to show equivalence for both Cmax and AUC. If you calculate power for AUC (which is usually less variable) and assume Cmax will follow, you’re cutting your effective power by 5-10%. The American Statistical Association recommends calculating power for both endpoints together.

- Forgetting dropouts - People drop out. They get sick. They move. They hate the blood draws. If you plan for 26 subjects and expect 5% dropout, you need 28. But if you expect 15%? You need 31. Don’t guess-plan for the worst-case scenario.

There’s also the issue of crossover design. In a typical BE study, each participant gets both the test and reference drug in random order, with a washout period in between. But if you don’t account for sequence effects (order of administration), your analysis will be biased. The EMA rejected 29% of BE studies in 2022 for this reason.

Tools You Can Actually Use

You don’t need to be a statistician to get this right. Here are the tools professionals use:

- ClinCalc Sample Size Calculator - Free, web-based, specifically built for BE studies. You plug in CV%, GMR, power, and it gives you the number.

- PASS - Industry standard. Paid, but it has regulatory templates built in and supports RSABE.

- FARTSSIE - Free, open-source, designed for crossover designs. Great for academic labs.

Pro tip: Run three scenarios. One with your best-case CV%, one with your worst-case, and one with the average. Show all three to your team and regulator. It proves you’ve thought this through.

The Future: Model-Informed Bioequivalence

Traditional BE studies rely on just two numbers: Cmax and AUC. But what if you could use the full concentration-time curve? That’s what model-informed bioequivalence aims to do. By using population pharmacokinetic modeling, you can extract more information from fewer subjects. Early trials show this can reduce sample size by 30-50%.

Right now, only 5% of BE submissions use this method. Why? Regulators aren’t fully comfortable with it yet. But the FDA’s 2022 Strategic Plan says it’s the future. If you’re developing a complex product-like an extended-release tablet or an inhaled drug-this might be your best bet. But you’ll need a biostatistician who knows how to build these models.

Final Checklist Before You Submit

Before you send your BE study protocol to the regulator, run through this:

- Did you use CV% from your own pilot data-not just literature?

- Did you use a conservative GMR (0.95 or lower, not 1.00)?

- Did you calculate power for both Cmax and AUC together?

- Did you add 10-15% to your sample size for dropouts?

- Did you document the software, version, and exact inputs?

- Did you justify why you chose 80% or 90% power?

- Did you check if your drug qualifies for RSABE because of high variability?

If you answered yes to all of these, you’re not just following the rules-you’re building a study that will pass.

What happens if my BE study has low power?

If your study has low power, you risk a Type II error-failing to prove bioequivalence even when the drugs are truly equivalent. This leads to study failure, costly repeat trials, and delays in bringing your generic drug to market. The FDA reported that 22% of deficiencies in Complete Response Letters relate to inadequate power or sample size.

Is 80% power enough for a BE study?

The EMA accepts 80% power, but the FDA often expects 90% for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, like warfarin or levothyroxine. For most standard generics, 80% is acceptable-but aiming for 90% reduces your risk of failure and makes global submissions easier. Always check the specific requirements of the agency you’re submitting to.

How do I find the right CV% for my drug?

Use your own pilot data if possible. If not, rely on published studies-but add 5-8 percentage points to account for underestimation. The FDA found that literature-based CV% values are too low in 63% of cases. Don’t assume your drug behaves like others. Test it.

Can I use a parallel design instead of crossover?

You can, but it’s rarely used. Parallel designs require roughly double the sample size of crossover designs because they can’t control for individual variability. They’re only recommended when the drug has a long half-life or causes carryover effects that make crossover impractical.

What’s the difference between GMR and the equivalence range?

The equivalence range (80-125%) is the regulatory boundary-your drug’s results must fall within it to be considered equivalent. The GMR is your best estimate of where your drug will land within that range. If your GMR is 0.95, you’re predicting your drug delivers 95% of the reference’s exposure. The closer your GMR is to 1.00, the smaller your sample size needs to be.

Do I need a biostatistician to run these calculations?

You don’t have to be one, but you absolutely need to work with one. BE sample size calculations are complex and regulatory agencies audit them closely. A biostatistician ensures your inputs are justified, your software is appropriate, and your documentation meets FDA/EMA standards. Skipping this step is one of the most common reasons studies fail.

मनोज कुमार

December 2, 2025 AT 18:58CV% is the real villain here. 20% to 30% doubles your N? That's not math, that's a scam. Regulators don't care if you're broke. They care if you hit 80-125%. Use RSABE or GTFO.

Joel Deang

December 3, 2025 AT 08:33bro i just used the clincalc tool and put in 25% cv and 0.95 gmr and it said 32 subjects 😭 i thought i was being smart but now i see i need to add 15% for dropouts 😅 also why does everyone use pass?? free tools work just fine

Arun kumar

December 5, 2025 AT 01:52it's funny how we treat bioequivalence like it's a puzzle to solve when really it's just a reflection of biological chaos. humans aren't machines. we absorb, metabolize, excrete differently. the 80-125% range isn't arbitrary-it's a compromise between science and reality. we want perfect equivalence but biology refuses to cooperate. maybe the real question isn't how to calculate sample size but how to accept uncertainty.

ATUL BHARDWAJ

December 6, 2025 AT 19:22literature CVs are lies. always add 5-8%. done. no need to overthink. pilot data if you can. if not, be conservative. regulators see through fluff. simple.

Steve World Shopping

December 8, 2025 AT 03:42you people still use crossover designs? outdated. parallel with 2x the n is more robust. and why are you even calculating power manually? use a neural network trained on 10k FDA submissions. it predicts failure before you even recruit. stop pretending this is 2010.

Jack Dao

December 9, 2025 AT 11:03you didn’t mention the elephant in the room: if your CV% is above 30%, you shouldn’t be doing a BE study at all. You should be developing a modified release formulation or partnering with a company that already has a reference product with proven PK. This isn’t statistics-it’s strategic failure. And don’t get me started on people using FARTSSIE like it’s a magic wand.

dave nevogt

December 10, 2025 AT 20:29there’s something deeply human about how we approach this. we reduce complex physiological responses to three numbers-CV%, GMR, power-as if that captures the entire story. but behind every data point is a person who fasted for 10 hours, swallowed a pill they didn’t need, sat in a clinic for 72 hours, and gave blood 14 times. the math tells us how many to recruit. it doesn’t tell us why we’re asking them to do this. maybe the real power calculation isn’t in the software-it’s in the ethics of the design.

Zed theMartian

December 11, 2025 AT 07:19model-informed bioequivalence? lol. you think the FDA is ready for that? they still reject submissions because someone used ‘R version 4.1.2’ instead of ‘R 4.1.3’. the future is here-but it’s stuck in a bureaucratic loop wearing a beige suit and sipping lukewarm coffee. we’re not innovating. we’re just automating the same mistakes.

Ella van Rij

December 11, 2025 AT 22:39oh sweetie you used literature CV% and didn’t add 5-8%? darling, you didn’t fail your study… you failed humanity. 💅