Medication mistakes at home are more common than you think

Every day, people take pills, liquids, or patches at home without a second thought. But what if the pill you just gave your child was meant for someone else? What if you doubled the dose because you forgot you already took one? These aren’t rare accidents-they happen more often than most realize. In the U.S., medication errors at home harm over 1.5 million people each year. For kids under six, a medication mistake occurs every 8 minutes. And for older adults on five or more medications, the risk jumps by 30%.

The problem isn’t laziness or carelessness. It’s complexity. Medications come in confusing forms, labels are hard to read, instructions change without warning, and memory fades fast. A study found that 40% to 80% of what patients hear at the doctor’s office is forgotten or misunderstood by the time they get home. That’s not a failure of will-it’s a system failure.

What are the most common medication mistakes?

Not all errors are the same. Some are small, others can land someone in the hospital. The most frequent mistakes include:

- Wrong dose: Giving too much or too little. This is especially dangerous with children’s medicines. Infant Tylenol is five times more concentrated than children’s Tylenol. Mixing them up can cause liver damage.

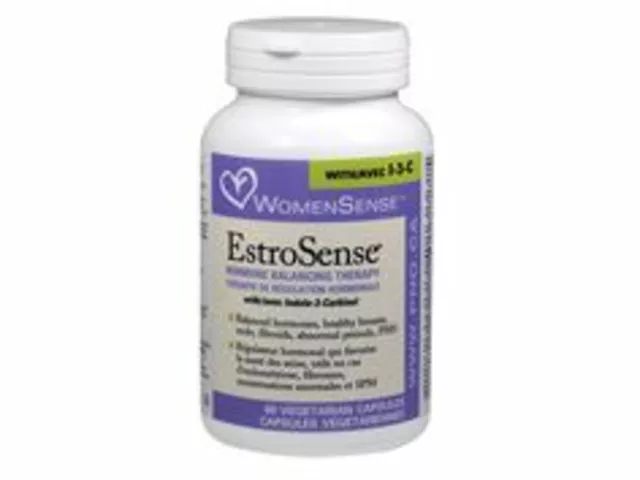

- Wrong medication: Taking someone else’s pills by accident. Or grabbing a bottle that looks similar-like confusing Hydroxyzine with Hydralazine.

- Missing doses: Skipping pills because you’re busy, forgetful, or afraid of side effects. One study showed 92.7% of parents gave fewer antibiotic doses than prescribed for ear infections.

- Wrong timing: Taking meds at the wrong time of day. Some drugs need to be taken on an empty stomach. Others must be taken with food. Getting this wrong changes how well they work.

- Double dosing: Taking another pill because you think you missed one. You might’ve taken it, but forgot. Or you took it, but didn’t realize it was a combination pill that already included the same ingredient.

- Keeping expired or discontinued meds: Old antibiotics, unused painkillers, or leftover blood pressure pills sit in drawers for months. People grab them when they feel sick, not realizing the prescription was canceled or the drug is no longer safe.

- Combining meds unknowingly: Giving a cold medicine that already has acetaminophen, then adding Tylenol on top. That’s how liver damage happens.

Why do these mistakes keep happening?

It’s not just about forgetting. The system is stacked against people trying to do the right thing.

Doctors often write prescriptions by hand. Pharmacies print labels in tiny font. Medications have similar names-Glipizide and Glyburide look alike and sound alike. One study found that look-alike/sound-alike drugs caused 25% of all medication errors in home care.

Health literacy plays a huge role. If you don’t understand what “take twice daily” means-or if English isn’t your first language-you’re more likely to mess up. Many patients leave the clinic thinking they know what to do… only to realize hours later they didn’t understand half of what was said.

For older adults, the problem multiplies. If you’re taking eight different pills, each with different times, food rules, and side effects, it’s easy to get lost. One study found that people over 75 are 38% more likely to make a medication error.

And then there’s cost. People skip doses because they can’t afford refills. They cut pills in half to stretch supplies. They stop antibiotics early because they feel better. All of these are mistakes-and all of them are preventable.

How to avoid medication errors at home

You don’t need to be a nurse to keep your family safe. These simple steps cut risk dramatically.

- Keep a real-time medication list. Write down every pill, liquid, patch, or injection you or your loved one takes. Include the name, dose, time, and reason. Update it every time something changes. Show this list to every doctor, pharmacist, or nurse you see-even if they say they already have it.

- Use a pill organizer with clear labels. Don’t rely on memory. Buy a weekly or daily organizer with big, easy-to-read labels. Fill it yourself, or have someone help you. If you’re using a multi-dose pack from the pharmacy, double-check the pills inside before you put them in the box.

- Always check the label. Before you give any medicine, read the name, dose, and instructions. Don’t assume it’s the same as last time. Look at the bottle, not the box. Look at the liquid, not the dropper. Check the concentration. For children, always match the dose to their weight, not their age.

- Never mix medications without asking. Cold medicines often contain acetaminophen or ibuprofen. If you’re already giving one of those for fever, adding another can overdose your child. Always ask: “Does this have the same active ingredient?”

- Use the teach-back method. When a doctor or pharmacist explains your meds, say: “So, just to make sure I got this right-you want me to give my mom 5 milliliters of this liquid twice a day, after breakfast, for seven days. And I shouldn’t give her anything else with acetaminophen?” If you can’t repeat it back clearly, ask again.

- Store meds safely and out of reach. Keep all medications locked up or in a high cabinet-not on the counter, not in the bathroom. Kids, pets, and even confused older adults can grab the wrong bottle quickly.

- Dispose of old or unused meds properly. Don’t flush them or toss them in the trash. Take them to a pharmacy drop-off or a local drug take-back day. If you’re unsure, call your pharmacy. Expired or unused meds are a major source of accidental poisoning.

- Set reminders. Use phone alarms, sticky notes, or a smart speaker. Say: “Alexa, remind me to give Dad his blood pressure pill at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m.”

Special risks for children and seniors

Children and older adults face unique dangers.

For kids: Parents often alternate Tylenol and Advil to control fever. But research shows this increases the chance of a dosing error by 47%. Stick to one, and follow the weight-based chart on the bottle. Never use a kitchen spoon to measure liquid medicine. Use the dropper, syringe, or cup that came with it. And never give adult medicine to a child-even a small amount can be deadly.

For seniors: If someone is on five or more medications, they’re at high risk. Simplify the regimen. Ask the doctor: “Can any of these be removed?” or “Can we combine them into one daily dose?” Use a blister pack from the pharmacy. Make sure someone checks in daily to confirm pills were taken. Watch for signs of confusion, dizziness, or falls-these can be side effects of a wrong dose.

What to do if a mistake happens

If you realize you gave the wrong dose, the wrong medicine, or too much:

- Don’t panic. Stay calm.

- Check the medicine bottle for poison control info. Most have a number on it.

- Call your local poison control center immediately. In New Zealand, that’s 0800 764 766. In the U.S., it’s 1-800-222-1222.

- If the person is having trouble breathing, passing out, or having seizures, call emergency services right away.

- Take the medicine bottle with you to the hospital or clinic.

Most errors don’t lead to disaster-but they can. The sooner you act, the better the outcome.

Ask your doctor: Three questions to prevent errors

Before leaving any appointment, ask these three questions:

- What is this medicine for? Don’t settle for “it’s for your blood pressure.” Ask: “What will it actually do in my body?”

- What happens if I miss a dose? Should you take it late? Skip it? Double up? Know the answer ahead of time.

- Are there any other medicines or foods I should avoid? Grapefruit, alcohol, antacids-these can interfere with meds in dangerous ways.

These questions take 30 seconds. They can save a life.

Bottom line: Safety is a habit, not a one-time fix

Medication safety isn’t about being perfect. It’s about building systems that protect you when you’re tired, distracted, or overwhelmed. A labeled pill box. A written list. A phone alarm. A poison control number saved in your contacts. These aren’t fancy tools-they’re lifelines.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people are hurt because of simple mistakes. But most of these errors can be stopped-with awareness, preparation, and a little help from the people around you.

Start today. Write down your meds. Check the label. Ask one question. You might just prevent the next mistake before it happens.

Shawn Peck

January 30, 2026 AT 16:10This is the most basic stuff. If you can't read a label or count to two, maybe don't give meds to kids. I've seen grandparents give adult ibuprofen to toddlers because 'it's just a pill.' No. Just no. You're not a hero. You're a liability.

And don't get me started on people who keep old antibiotics in their bathroom cabinet like they're emergency snacks. That's not 'being prepared'-that's playing Russian roulette with liver failure.

Gaurav Meena

February 1, 2026 AT 08:39I work as a pharmacy tech in India and I see this every single day 😔

People buy antibiotics over the counter without a prescription because they 'know what they need.' Then they stop after 2 days because they 'feel better.' I always hand them a little card with the medicine name, dose, and a drawing of a clock for timing. Simple. Visual. Works wonders.

And yes-kids' Tylenol vs. infant Tylenol? That’s a nightmare waiting to happen. One drop too much and you’re in ER. Please, please, please use the syringe. Not a spoon. Not a teaspoon. The syringe.

Beth Beltway

February 1, 2026 AT 11:12The article says 'it's a system failure' like that somehow excuses people. No. It’s personal responsibility. If you can’t manage five pills, don’t take five pills. Stop blaming the font size on the label. Your brain is the tool here. Not the pharmacy’s printer.

And for the love of God, if you’re mixing cold medicine with Tylenol, you’re not 'being thorough'-you’re just a walking overdose waiting to happen. I’ve seen three ER cases this year from this exact mistake. All from people who 'didn’t realize.' Didn’t realize? You didn’t read. That’s not ignorance. That’s negligence.

Natasha Plebani

February 2, 2026 AT 15:16The epistemological rupture between clinical intent and domestic execution is profound. The pharmacological literacy deficit is not merely a cognitive gap-it’s a structural alienation from the symbolic economy of pharmaceutical signifiers. Labels are not merely text; they are semiotic traps designed for an idealized, neurotypical, English-dominant, high-literacy subject.

When a patient encounters 'take twice daily' without context of circadian pharmacokinetics, the instruction becomes an act of faith, not comprehension. The system doesn't fail-it was never designed to be comprehended by the very population it purports to serve. The pill organizer is not a solution-it’s a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage.

Kelly Weinhold

February 4, 2026 AT 06:10I love how this post doesn’t just list problems-it gives real, doable fixes. I started using a pill box after my mom had a scare with her blood pressure meds. Now we do a weekly check-in every Sunday. I fill it, she checks it, we laugh about how we forget what 'BID' means.

And I saved poison control in my phone under 'EMERGENCY' with a red icon. My kids know to call it if they ever see Grandma looking weird after a pill. It’s not scary-it’s just smart. Small habits = big safety nets. You don’t need to be perfect. Just consistent.

Kimberly Reker

February 5, 2026 AT 11:46My grandma used to keep all her meds in a shoebox under the bed. I found it last year. Six different bottles, expired antibiotics, half-used painkillers from 2018, and a bottle labeled 'for pain' with no name. I cried.

We got her a weekly organizer, set phone alarms, and I made a color-coded chart with pictures. She calls me every morning now to say she took her pills. It’s not about control-it’s about connection. And yeah, I still check the label before I hand her anything. Always.

Eliana Botelho

February 6, 2026 AT 19:31Okay but have you considered that maybe people just don’t care? Like, really? You’re telling me the real problem is that labels are too small? That’s cute. The real problem is that people don’t read. Ever. They don’t ask questions. They don’t call their doctor. They just grab the bottle that looks like the one from last time and hope for the best.

And the 'teach-back method'? That’s for people who still believe in healthcare as a benevolent institution. Most patients are too overwhelmed, too tired, too poor to care if they understand 'hydroxyzine' vs. 'hydralazine.' They just want the headache to go away. Stop pretending education fixes systemic neglect.

Rob Webber

February 7, 2026 AT 13:53I’ve been a nurse for 22 years. I’ve seen parents give their 2-year-old a full adult dose of melatonin because 'it’s natural.' I’ve seen seniors take 12 pills at once because they thought 'it’s all for heart.' I’ve seen people mix alcohol with antidepressants and wonder why they passed out.

This isn’t a 'system failure.' It’s a cultural failure. We treat medicine like cereal-open, pour, eat. No thought. No respect. No consequences until it’s too late. And now we’re surprised when people die? Wake up.

calanha nevin

February 8, 2026 AT 11:15The most effective intervention is not the pill organizer or the label. It is the human connection. A phone call. A visit. A moment where someone says: 'Let me see your meds.'

Studies show that patients with regular medication reviews by a pharmacist or family member reduce error rates by 68%. Technology helps. But empathy scales. Make time. Ask. Listen. Repeat. That is the real safety net.

Lisa McCluskey

February 10, 2026 AT 06:03I used to be the person who skipped doses because I was 'fine.' Then I had a stroke from uncontrolled BP. Turns out I’d been taking half the dose for a year because I thought 'it was too strong.' I didn’t ask. I just assumed.

Now I keep a notebook. I write down every med, every time I take it. I show it to every doctor. I don’t care if they say they have it. I don’t trust their system. I trust my pen. Simple. Dumb. Works.