Nitroglycerin Environmental Impact: How This Medication Affects Water, Soil, and Wildlife

When you take nitroglycerin, a vasodilator used to treat angina and heart failure. Also known as glyceryl trinitrate, it works by relaxing blood vessels to improve oxygen flow to the heart. But what happens to the leftover drug when you flush unused pills or wash them down the sink? It doesn’t vanish. Nitroglycerin enters wastewater systems, survives treatment, and ends up in rivers, lakes, and even drinking water supplies. This isn’t theoretical—studies in Europe and North America have detected trace levels of nitroglycerin in surface water near hospitals and residential areas where cardiac medications are heavily used.

The real problem isn’t just nitroglycerin alone. It’s part of a larger group of pharmaceutical pollution, the accumulation of human-made drugs in the environment. Unlike natural substances, many drugs like nitroglycerin aren’t designed to break down easily. They linger. In water, even tiny amounts can disrupt fish reproduction, alter behavior in aquatic insects, and affect microbial communities that keep ecosystems balanced. One 2022 study in the journal Environmental Science & Technology found that nitroglycerin exposure caused reduced egg production in zebrafish at concentrations as low as 0.1 micrograms per liter—levels found in some wastewater outflows. And it doesn’t stop at water. When sewage sludge is used as fertilizer on farmland, nitroglycerin and other drugs can seep into soil, where they bind to organic matter and slowly leach into groundwater.

This isn’t about blaming patients. It’s about systems. Most people don’t know that flushing pills is one of the worst ways to dispose of medication. Yet it’s still common. And while pharmacies and hospitals have take-back programs, they’re often hard to access or poorly promoted. The drug disposal, the process of safely getting rid of unused or expired medications needs to be as simple as throwing out trash. But right now, it’s not. Meanwhile, wastewater treatment plants weren’t built to remove modern pharmaceuticals. They catch solids and bacteria, but not molecules like nitroglycerin. That means the drug slips through—and keeps going.

What can you do? Don’t flush. Don’t dump in the trash either—though that’s better than flushing. Look for local medication take-back events or drop-off bins at pharmacies. If none exist, mix unused pills with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal them in a container, and throw them in the regular trash. It’s not perfect, but it reduces the chance of water contamination. Also, support policies that require drug manufacturers to fund safe disposal programs. The environmental toxins, harmful substances that enter nature through human activity from medicines are real, measurable, and growing. And nitroglycerin is just one piece of a much bigger puzzle.

Below, you’ll find real stories, data, and practical advice from people who’ve looked deeper into how medications like nitroglycerin affect the world around us. These aren’t abstract warnings—they’re observations from the field, the lab, and the kitchen sink.

16 October 2025

16 October 2025

Nitroglycerin Environmental Impact: Tips to Reduce Harmful Effects

Learn how nitroglycerin can harm soil and water, and discover clear steps-take‑back programs, safe neutralization, and treatment technologies-to keep the environment safe.

Latest Posts

-

Experience the Magic of Delphinium: The Dietary Supplement That's Taking the Wellness World by Storm

-

The Impact of Diabetes Type 2 on Bone Health: Preventing Osteoporosis

-

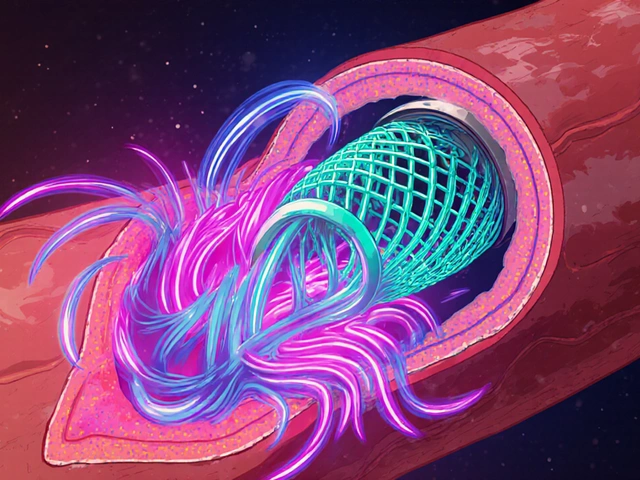

How High Blood Pressure Increases Risk of Blood Clots in Stents

-

Pancreatitis: Understanding Acute vs. Chronic and the Role of Nutrition in Recovery

-

Why Fermented Wheat Germ Extract is the Must-Have Dietary Supplement for Your Wellness Routine

13